|

While in chiropractic school, some of my colleagues and I used to tell the following joke:

Q: What is the definition of health? A: An incomplete work-up. Immersed in studies of endocrinology, obstetrics, orthopedics, etc., we were captivated by the detective’s game of diagnosis, the collection of data and its sorting and re-sorting into logical chains of decision making to arrive at a named condition: diabetes, carpal tunnel syndrome, migraine, etc. Everyone had something–at least everyone who came through our clinic doors did. That was the reason they were there. Our job, we were taught, was to find the problem and put a name on it so that we could treat it. If we could not find the diagnosis, we had no business offering treatment. So when the diagnosis was elusive, we had to look harder, be more clever detectives. If we interns were not clever enough we would look to our attending physicians for help, who in turn could consult with their department heads if they got stuck. If the head of a department could not make a reasonable diagnosis that meant there was nothing physically wrong, and the case was classified as ‘supratentorial’ (psychological or psychiatric in nature). During my internship I attended several patients with complaints such as fatigue, generalized body aches, insomnia, constipation, indigestion, etc., who never received a diagnosis and as such, never received treatment at our clinics or hospital. Their blood work, imaging studies, and urinalysis was normal. There was nothing really wrong with them, and such patients were dismissed or referred out for psychological or psychiatric evaluation. Our model, never explicitly stated but certainly transmitted to us through example, was that health was the absence of identifiable disease. A patient with symptoms but no disease was either a complainer, someone looking for attention, a person working the system for benefits of one kind or another, or a psychiatric patient, not a chiropractic one, healthy of body if not of mind. But what about patients with chronic pain who’d never had an injury, had no real findings on their exam other than tenderness, but who did not seem to be seeking attention, never stayed home from work, were not involved in litigation of any kind, did not have a Worker’s Compensation or Personal Injury claim, and who were paying hard-earned cash out of meager budgets to seek help from us? Fatigue, sleeplessness, body aches–these were common complaints, but they were symptoms not diagnoses. And what about the patients who came in for a yearly physical with no specific complaints, but were clearly obese and became winded just climbing up and down from the exam table? ‘Out-of-shape’ may not be a medical diagnosis but clearly such a person is not healthy. At the earliest stages of my clinical training I had a sense that health went beyond the mere absence of identifiable disease. Over time it became clear to me that, like any complex human descriptor, ‘health’ is not best described in dualistic terms of black or white. People were not simply either intelligent or stupid, tall or short, good or bad; and patients were not simply either healthy or sick. Health, it seemed to me, was a term that lent itself to infinite degrees of qualification depending upon factors objective (blood tests, physical examination, imaging studies) but also subjective (one’s sense of happiness and well-being).

0 Comments

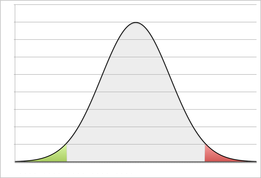

Since entering chiropractic college in 1984, I have been engaged in an ongoing process of developing and refining my own theory of health which is based on the concepts of function and well-being. When the systems of the body are functioning at their highest capacity and a presiding sense of satisfaction and well-being describes one’s condition of mind, a state of optimal health has been attained. When any of the body’s systems are functioning at very low capacity (or has ceased to function at all) there is disease. But in-between these extremes lie infinite variations in the level of physiological function and well-being, infinite degrees of health. Health, in my perspective, is something best understood not in dualistic terms ('sick' or 'healthy'), but as a continuum.

The optimal conditions for health seem to include: low or manageable stress levels, relatively low body fat percentage (under 15% for men, under 20-25% for women, depending on body type), good energy, sound sleep, effortless digestion, clarity of mind, habits of healthy eating and exercise, and the strength and endurance to be able to perform life’s tasks and activities easily and well. When one is at a high level of function a degree of good health is evident. But how many of us can say that their stress levels are truly as low as we need them to be? How many of us feel tired a lot of the time? Are healthy eating and exercise your daily habits? How about your waistline? When our lives become too busy for us to ever feel caught-up with our obligations, when we realize that it has been months or years since we engaged in regular exercise or physical play, when a truly great night’s sleep is an exception rather than the rule, when we find ourselves choosing the elevator over the stairs just to go up one or two flights, something has gone wrong. We may not have a diagnosable disease, but our level of function and well-being (our health) has been diminished. |

AuthorArchives

August 2021

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed